by Grant Wiggins & the Teaching staff

Admit it – I only read the list of six levels for the level Bloom’s taxonomynot the entire book that explains each level and the rationale behind the classification. Don’t worry, you are not alone: this applies to most teachers.

But this efficiency comes at a price. Many educators have a wrong view about classification and the levels in it, as the following errors indicate. Arguably the greatest weakness of the Common Core Standards is that they avoid being too careful in their use of cognitively focused verbs, similar to the rationale for the classification.

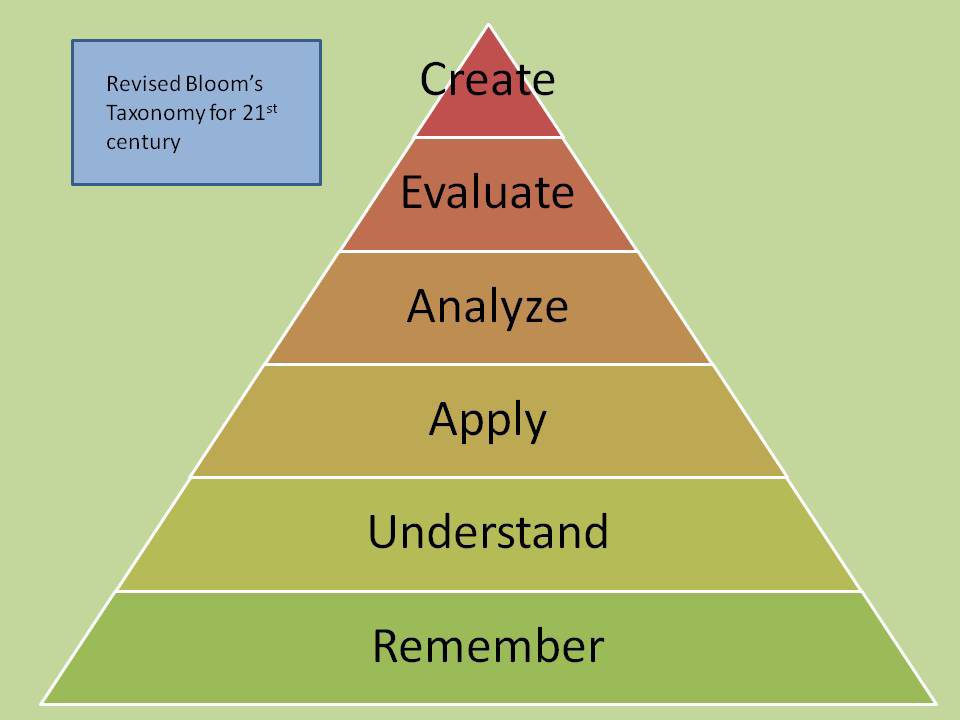

1. The first two or three levels of the classification involve “lower order” thinking while the last three or four levels involve “higher order” thinking.

This is not true. The only lower-order goal is “knowledge” because it uniquely requires mere recall on the test. Moreover, it is not logical to believe that “understanding” – 2Second abbreviation Level – requires only lower order thinking:

The basic behavior of interpretation is that when the student is communicated, he can identify and understand the main ideas contained within it as well as understand the interrelationships between them. This requires a gentle sense of judgment and caution in reading your thoughts and interpretations into the document. It also requires some ability to go beyond simply paraphrasing parts of the document to identify larger, more general ideas within it. The translator must also be aware of the limits within which interpretations can be drawn.

Not only is this higher order thinking – summary, main idea, conditional and careful thinking, etc. – a level that half of our reading students have not reached. By the way: the phrases “lower ranking” and “higher ranking” do not appear anywhere in the rankings.

2. “Application” requires practical learning.

This is incorrect, and is a misreading of the word “applied,” as the text explains. We apply ideas to situations, for example, you can understand Newton’s three laws or the process of writing but can you solve new problems related to them – without prompting? This application:

The entire cognitive domain of the taxonomy is arranged in a hierarchy, that is, each taxonomy within it requires lower skills and abilities in the order of taxonomy. The application category follows this rule in that applying something requires “understanding” the method, theory, principle, or abstraction being applied. Teachers often say: “If a student really understands something, he can apply it.”

A problem in a comprehension category requires that the student know the abstraction well enough to be able to demonstrate its use correctly when specifically asked to do so. But “application” requires a step beyond that. If a problem is new to the student, he or she will apply the appropriate abstraction without having to be asked to identify the correct abstraction or without having to be shown how to do so in this case.

Notice the key phrases: Due to New problem For the student, it will apply suitable Abstraction Without having to ask. thus, “Application” is actually a synonym for “transportation”.

In fact, the authors strongly emphasize the priority of application/transfer of learning:

The fact that most of what we learn is intended for application to problematic situations in real life indicates the importance of application objectives in the general curriculum. Thus, the effectiveness of a large part of the school program depends on how successfully students apply situations that students have never encountered in the learning process. Those who are familiar with educational psychology will recognize that this is the age-old problem of transfer of training. Research studies have shown that understanding an abstract idea does not guarantee that an individual will be able to apply it correctly. Obviously, students also need practice in restructuring and classifying situations so that the correct abstraction is applied.

Why UbD is what it is. Application problems must be new; Students must judge which prior learning applies, without prompting or prompting from supporting worksheets; Students must receive training and practice how to deal with non-routine problems. We designed UbD, in part, backwards from Bloom’s definition of to request.

As for the instructions supporting the transfer goal (and various… Types of transportation), The authors note this matter-of-factly:

“We have also attempted to systematize some of the literature on the growth, retention, and transfer of different types of educational outcomes or behaviors. Here we find very little relevant research. … Many claims have been made about different educational procedures … but they have rarely been supported by research findings.”

3. All verbs listed under each level of classification are more or less equal; They are synonyms for level.

No, there are distinct sub-levels of the classification, in which the cognitive difficulty of each sub-level increases.

For example, within knowledge, the lowest level of knowledge is knowledge of terms, where the most mnemonic form is knowledge of the main ideas, schemes, and patterns in a field of study, and where the highest level of knowledge is knowledge of theories and structures (e.g., knowledge of the structure and organization of Congress.)

Under Comprehension, the three sublevels in order of difficulty are translation, interpretation, and induction. The main idea of literacy, for example, falls under interpretation because it requires more than “translating” text into one’s words, as stated above.

4. Classification recommends against the goal of “understanding” in education.

Only in the sense that the term “understanding” is too broad. Rather, classification helps us more clearly define the different levels of understanding we seek:

To return to the illustration of the term “understanding,” the teacher might use the taxonomy to determine which of several meanings he or she means. If this means that the student was…aware of a situation…to describe it in slightly different terms than those originally used in describing it, then this corresponds to the taxonomic category ‘translation’ (which is a sublevel under comprehension). Deeper understanding will be reflected in the next higher level of classification, ‘explanation’, where the student is expected to summarize and explain… There are other levels of classification that the teacher can use to indicate deeper ‘understanding’. “

5. The authors of the classification were confident that the classification was a valid and complete classification

No they weren’t. They note that:

“Our attempt to rank learning behaviors from simple to complex has been based on the idea that a given simple behavior may combine with other equally simple behaviors to form a more complex behavior… Our evidence for this is not entirely satisfactory, but there is an unmistakable error in which the trend points toward Hierarchy of behaviors.

They were particularly concerned that there was no single theory of learning and achievement –

“It took into account the types of behaviors represented in the educational objectives that we tried to classify. We were reluctantly forced to agree with Hilgard that every theory of learning explains some phenomena very well but is less adequate in explaining other phenomena. What we need is a synthetic theory of learning that is larger than it seems.” Available at present.

Subsequent schemes – such as the Web’s Depth of Knowledge and the Revised Taxonomy – do nothing to solve this fundamental problem, with implications for all modern standards documents.

Why is all this important?

Arguably the greatest failure of the Common Core Standards is that these issues are overlooked through the arbitrary/negligent use of verbs in the standards.

There appears to have been no attempt to achieve accuracy and consistency in the use of the verbs contained in the standards, making it almost impossible for users to understand the level of precision set forth in the standard, and therefore the levels of precision required in local assessments. (Nothing is said in any documentation about how intentional these verb choices are, but I know from my previous experience in New Jersey and Delaware that verbs are used randomly – in fact, writing teams start changing verbs just to avoid repetition!)

The problem is already clear: in many schools, assessments are less rigorous than the standards and practice tests clearly require. No wonder the scores are low. I’ll have more to say about this issue in a later post, but my previous posts about standards provide additional background on the problem we face.

to update: Already, people argue with me on Twitter as if I agree with everything said here. I am not saying here that Bloom was right about the classification. (His doubts about his work indicate my true opinions, don’t they?) I’m just quoting what he said and what is commonly misunderstood. Indeed, I am rereading Bloom as part of a critique of taxonomy in support of the third revised edition of the UbD in which we call for a more developed view of the idea of depth and rigor in learning and assessment than currently exists.

This article first appeared on Grant’s personal blog; Scholarship can be found On Twitter here; 5 common misconceptions about Bloom’s taxonomy; Attribute the image to Flickr user langwitches