This article is part of the US-China Dynamics series, edited by Muqtedar Khan, Jiwon Nam and Amara Galileo.

When one thinks of Latin America from outside the region, they seem to be faced with a group of homogeneous countries, with similar language, culture and history. However, despite the links that unite them, the interests of Mexico and Central American countries, closely linked to the United States, are different from South America’s priorities. On the one side, Brazil and Argentina – large countries with a global presence, inserted within the Río de la Plata basin and with projection towards the Atlantic Ocean; on the other hand, the Andean Countries – smaller and with interests in the Pacific Ocean. The Andean countries are defined not only by the importance that the Andes – the mountain range that crosses South America from north to south – acquire for them but also by its belonging to the Andean Community. This organization, created in 1969, initially comprised Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. Venezuela would then join in 1973, while Chile would withdraw in 1976. Decades later, in 2006, Venezuela would also withdraw from this supranational organization.

This research seeks to elaborate on the current competition between China and the United States to exert influence in the Andean region countries. To do so, considering the most important factors in the power transition (or hegemonic change) scenarios developed by Robert Gilpin (1981), emphasis will be placed on what is happening in economic (trade, investment and finance), technological, political and military matters, mainly in the second decade of the 21st Century. The premise of this research is to demonstrate that the presence of China has increased in recent years, but this is not only unequal, depending on the field, but it is also manifested in a greater deal in certain countries, such as Venezuela. Despite the abovementioned, China does not define its link with Andean countries in terms of ideology, as can be seen from the progress made with countries that have had left-wing governments (Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela) and with those mainly liberal (Chile, Colombia and Peru).

On its side, the United States keeps great influence in Latin America, even though its presence in the Andean region has been questioned in those countries with progressive administrations. And even if this part of the world (in comparison to others), does not constitute the most important region to the interests of China, the United States shows great concern regarding the advance of the Asian power and the changes that can generate a greater influence of China in its historic “backyard”. Finally, although the competition between China and the United States is real, this does not reach such alarming levels that puts the Andean region’s interests at risk. Nevertheless, this research will intend to set scenarios that help understand situations that may be generated in the short term, and that, considering the importance that both global powers have to Andean countries, will force the latter to make difficult decisions in these matters.

Economic competition

Trade

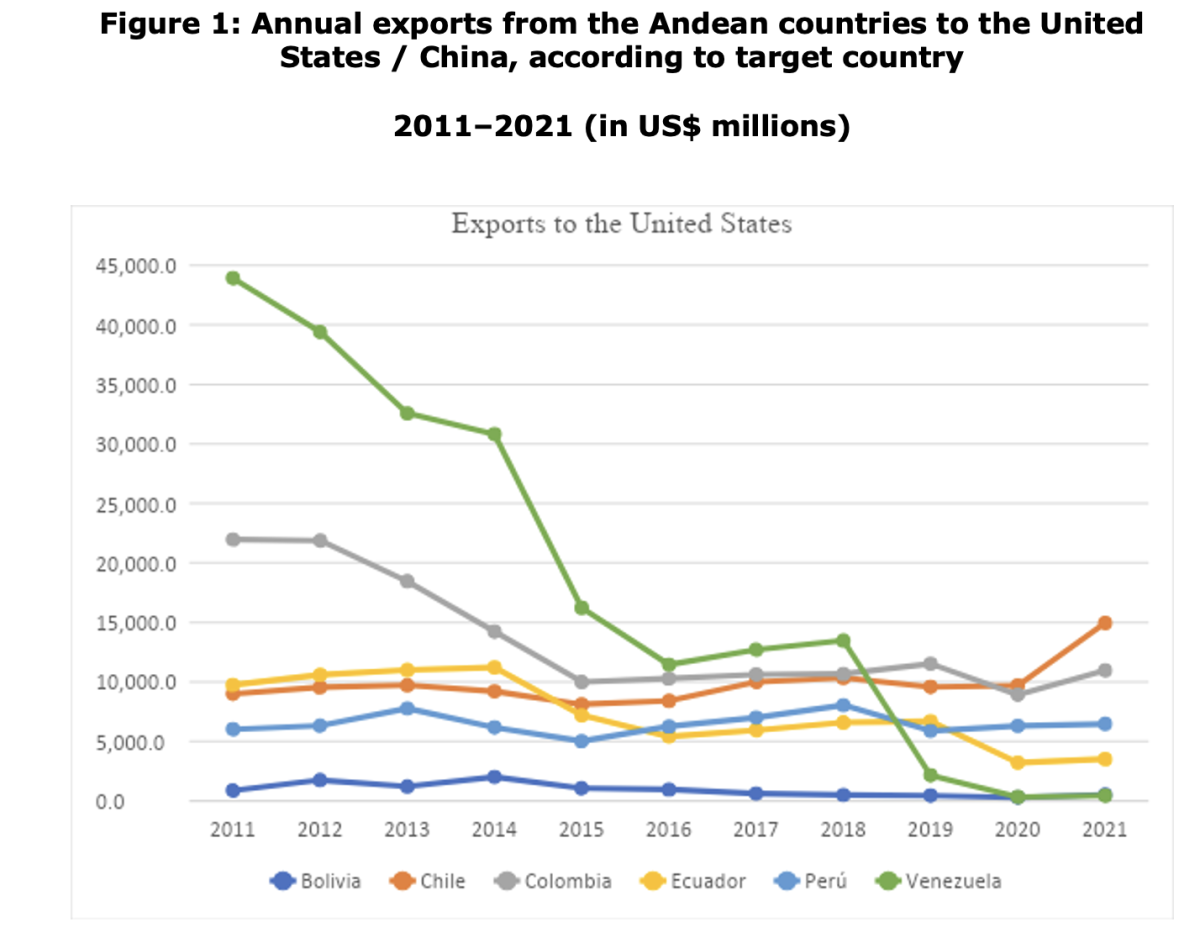

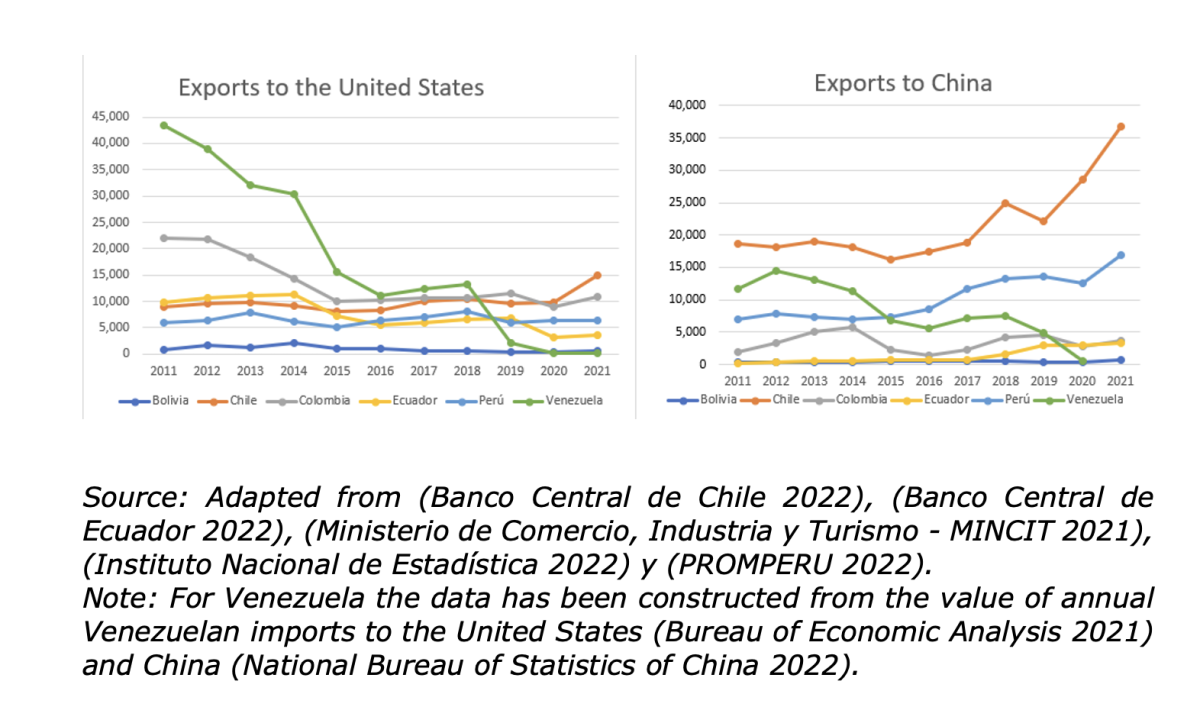

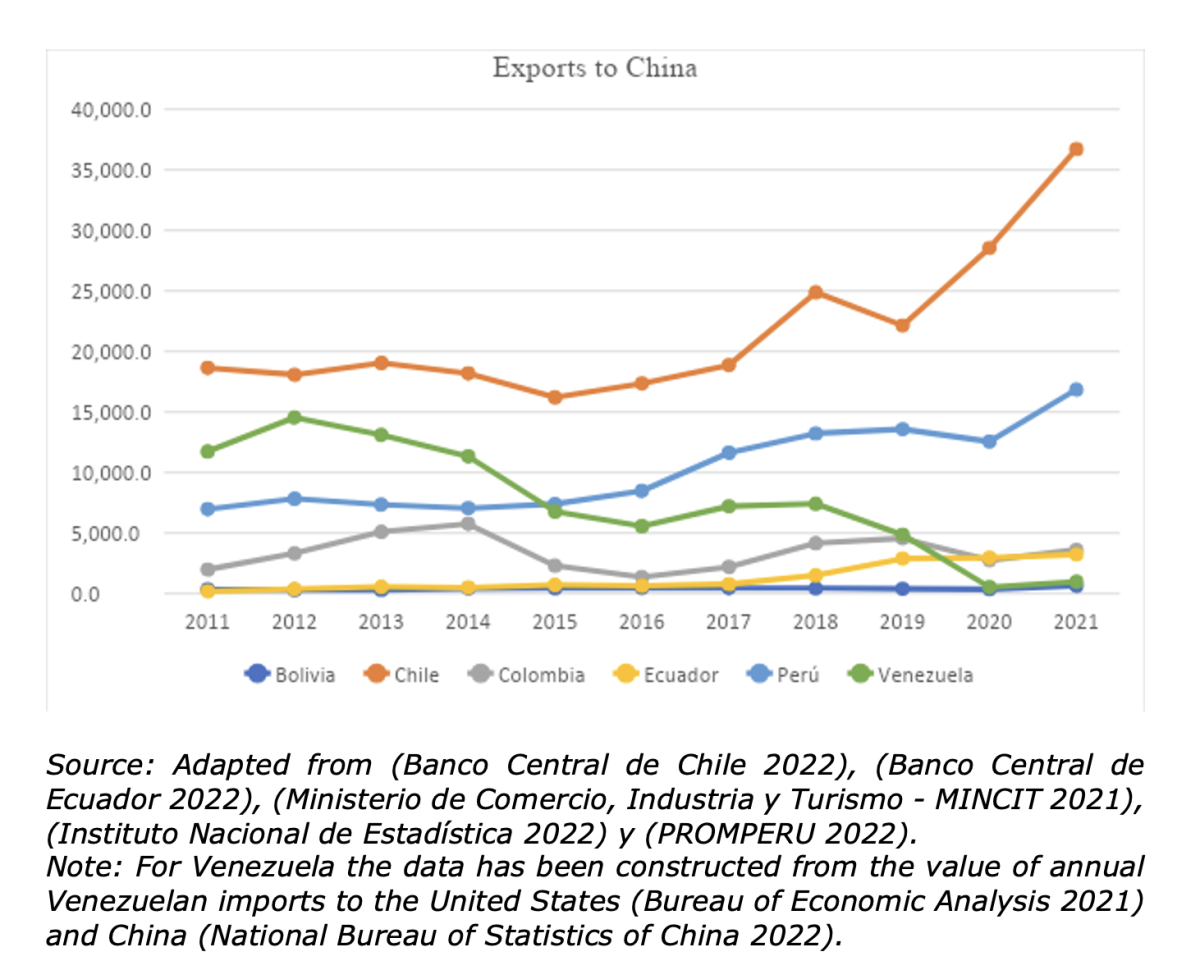

In commercial terms, in the last decade, important changes have occurred in Latin America. Before 2010, the United States was one of the main trading partners in the region, if not the most important. However, this commercial relationship was weakened in the following years, especially in the Andean countries. Thus, over the past ten years, there has been a trend towards an increase in the value of the exports to China, meanwhile, the value of the exports to the United States could have stalled or decreased in certain cases (illustrated in Figure 1). One of the main reasons why China’s trade participation in the Andean countries is increasing is due to its need of basic products from primary-extractive activities. For this reason, it is not a surprise that two nations with great mining activity, i.e. Chile and Peru, have China as their main trading partner. These two Andean countries are the ones that showed a greater increase in their exports to the Asian country in the last decade, maintaining their trading dynamic towards the United States without much variation.

On the other hand, Colombia and Ecuador have China among their main trading partners, with a greater projection in the Ecuadorian case, to the point that in that country, China competes with the United States as the main destination of its exports. In the case of Colombia, even though exports towards the United States have decreased considerably in the last decade, trade with China has also stagnated, resulting in the United States as its main partner. A particular case is Venezuela, whose foreign trade is characterized by the predominance of the exports of oil and its derivatives. Its conflictive relationship with the United States and the many sanctions in economic sectors that the Caribbean country has received since 2008 make the exports to the northern country decrease more than in any other Andean country. This situation has led Venezuela to seek new partners that purchase oil, as has been the case of China. And, although the export numbers may seem to have decreased since 2018, energy cooperation between China and Venezuela has been maintained through loans and investments granted by Beijing, which have arranged payments based on oil exports (Giuseppi 2020).

For the Trump administration, China was a strategic competitor that sought to be weakened. Despite this, a decision was made to move away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Although Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross had announced that the withdrawal from the TPP did not mean a breaking point in its relationship with the countries involved in the agreement, the TPP was a geopolitical strategy of the Obama administration to set the American leadership in Asia, which is why its withdrawal was seen as a great advantage for China (Merino 2019). Since the early 21st century, China’s strategy implied the establishment of a network of trade agreements around the world. This trade expansion started before the so-called Trade War with the US (even with certain American support), which led the Asian nation to advance freely in its trading relations. With all this in mind, it is not a surprise that, in terms of trade, China has been able to grow rapidly in the region.

Investments

Although American direct investments are more meaningful in Latin America – the Colombian case is an emblematic one – the growth of the Chinese investments focused on sectors of the economy that were not considered in the past (Detsch 2018), thereby generating an optimistic climate in the region. These flows of Chinese Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) are characterized mainly for the seeking of projects in which the supply of natural resources is ensured, even though these do not get immediate profits. 90 per cent of Chinese investments in Latin America belong to this sector. The hydrocarbon sector stands out, especially the China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC), which, since the 90s, has operated mining projects in Venezuela, Peru and Ecuador through state concessions.

Regarding the mining sector, the main destination of Chinese investments has been Peru and, more recently, Ecuador. This has led China to have the largest amount of copper produced by these states in its possession (Svampa and Slipak 2015). But, besides the acquisition of extractive industries companies, Chinese firms have also prioritized investments, through fusions and acquisitions, in companies of generation and distribution of electrical energy, and of basic services such as gas and water. In this framework, China entered the electricity sector in the Andean region in 2020, acquiring mainly the assets of the US company Sempra Energy, which is in charge of electrical distribution in Chile and Peru. The substitution of US capital for Chinese firms indicates the superior payment capacity that these possess when it comes to energy assets. China has also made large investments in infrastructure in the Andean region, such as the purchase of the “Terminales Portuarios Chancay” (Peru) company – a multipurpose port terminal that aims to become the hub between Asian products and the Pacific coast of South America. The completion of this megaproject will benefit China’s trade with Peru, and its Andean neighbors Bolivia, Chile, Ecuador and Colombia.

In sum, in terms of investments, the sectors in which China has influence are considered to be of a strategic importance to the economic development of all parties. It is evident that, besides the existent differences, ‘China has been able to set the ground to deepen future cooperation in a region of great importance to the US’ (U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission 2021, 101–102).

Finances

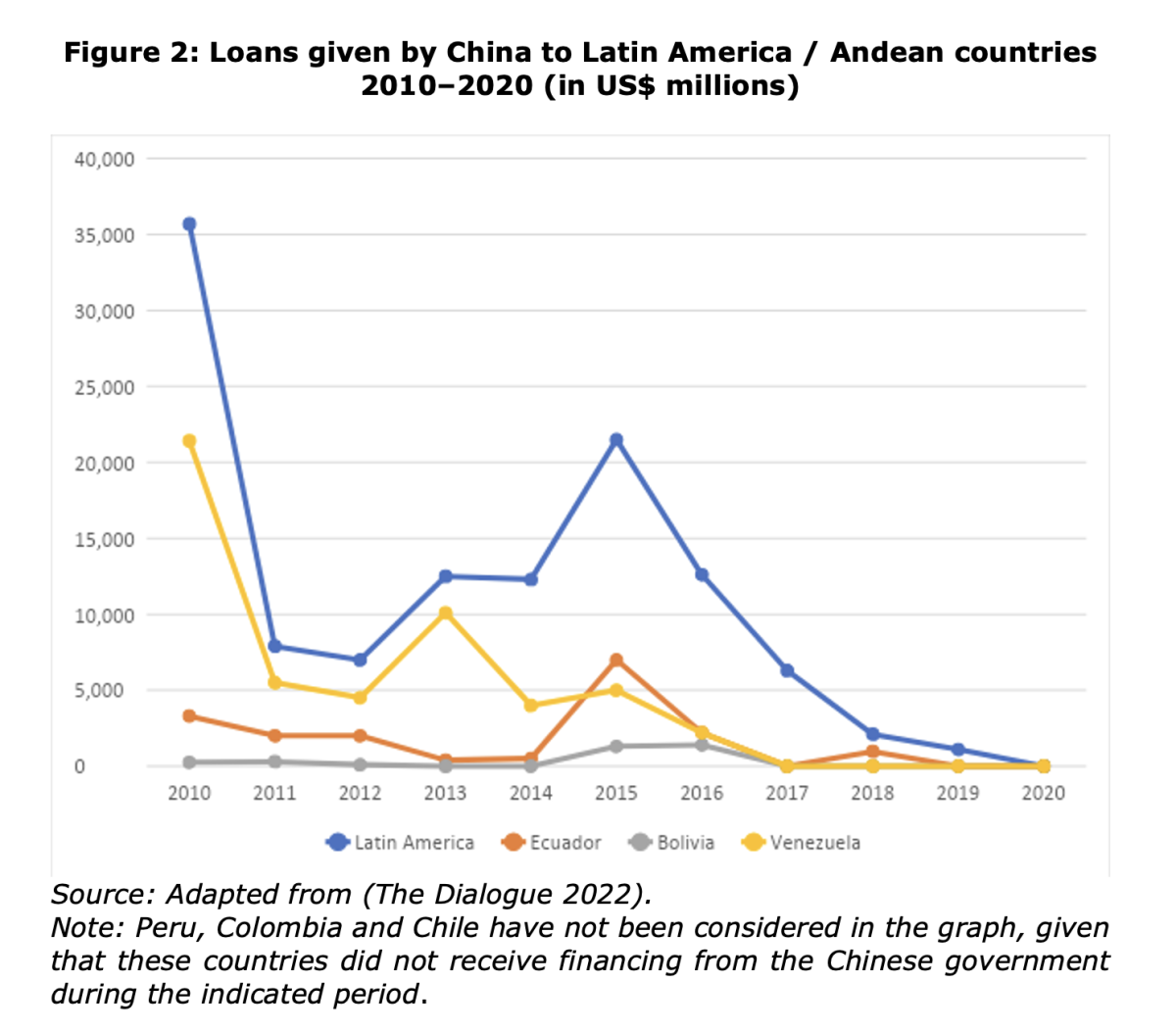

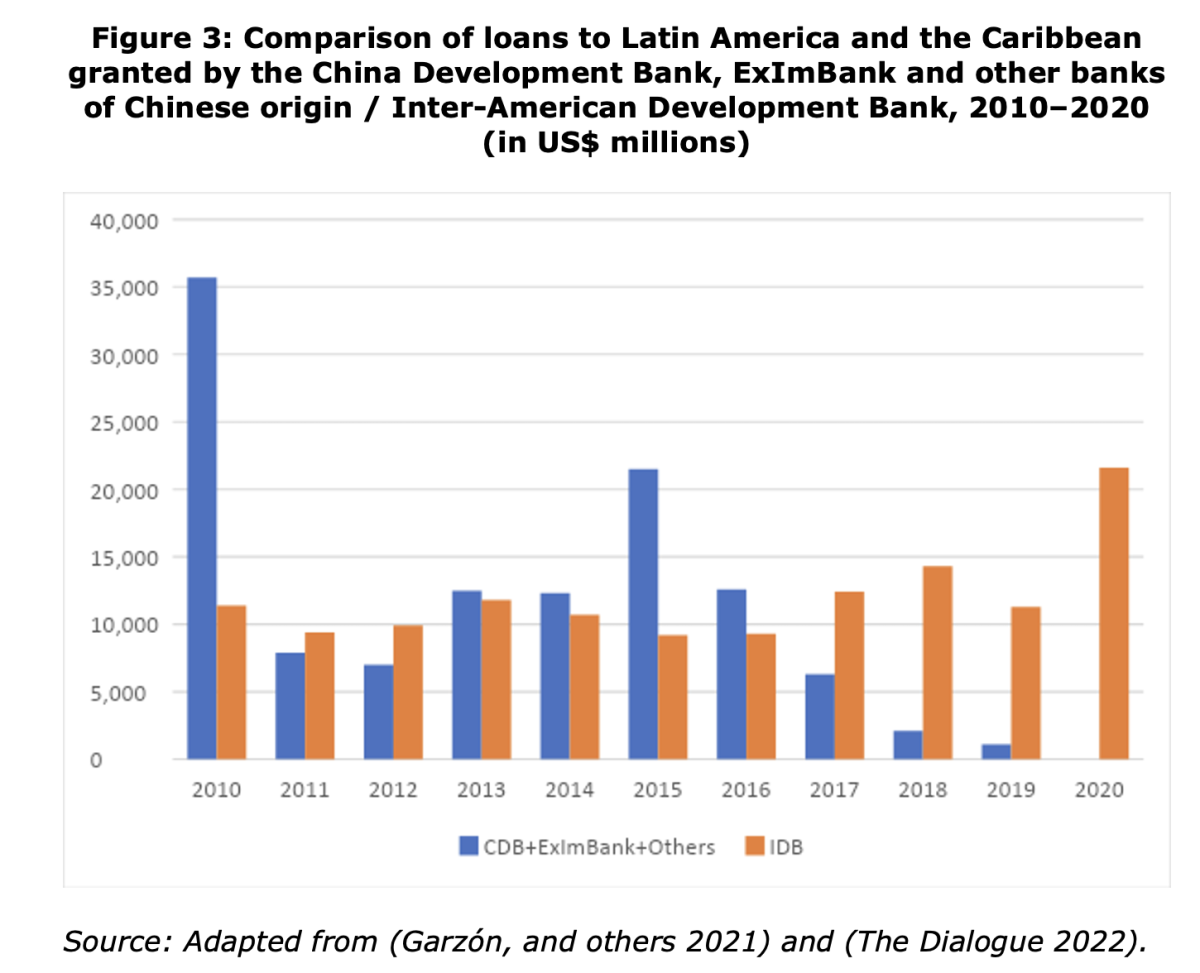

Since the early 20th century, the Chinese financial presence in Latin America has grown significantly, especially through the role of the China Development Bank (CDB) and the Export-Import Bank of China (ExImBank). Though this presence has drastically decreased in recent years. In that sense, regarding the Andean region specifically, although Chinese loans to this part of the world went from around US$8 billion in 2011 to US$13 billion in 2015, this figure then reduced to US$6 billion in 2016, to then almost disappear (explained further below). The reduction of Chinese loans since 2018, with 2020 the breaking point, as for the first time in 15 years (since 2006), Latin America stopped receiving public financing from China. Nevertheless, the Andean region may have suffered the most from this depletion, to the point in which, excluding the loans that Ecuador received in 2018 (US$ 969 million), the last year when the rest of the countries received bilateral financial support was in 2016.

In spite of what has happened to some countries in the Andean region (like Venezuela and Ecuador), Chinese loans have been fundamental in contexts that were not favorable. Through the 21st century, the China Development Bank (CDB) has had Venezuela, Brazil and Ecuador, in that order, as the most benefited countries in Latin America, meanwhile the Export-Import Bank of China (ExImBank) has had Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia. China has known how to approach countries that not only have had differences with the United States and with Western finances, but also have low credit rating, such as Venezuela, Ecuador and Bolivia. Chinese loans ‘are exempt from political conditionality as that of the IMF and WB, which require the application of austerity measures and structural adjustment programs; they become less onerous than the ones obtained through international credit markets; they are for significant sums; long-term (up to twenty years); and their processing (two years or less) are more expeditious than those of similar operations in banks and international financial institutions’ (Molina Díaz and Regalado Florido 2017, 111).

It could be added that most of these loans, from which the cases of Venezuela and Ecuador are representative, were “loans for oil”. The paradox is that countries such as Peru and Chile have other resources that are of interest, but did not receive Chinese financing (Gallagher, Irwin and Koleski 2013, 6). Regarding Venezuela, during the first years of its economic crisis (2014–2016), China was an important backing to the Chavista regime. Beijing had agreed on giving it better conditions to pay for its credits and access to new credit, and, in exchange, Venezuela would send more oil (Ghotme-Ghotme and Ripoll De Castro 2016, 46). The US government has been critical of this financing, as it would have allowed the survival of the government of Nicolas Maduro without a clear benefit for its population (Pu and Myers 2021, 10). As expected, the threat posed by China’s presence in the finance field has implied not only questioning by the United States, but also a response using multilateral financial organizations as tools, such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), a rather emblematic case.

For many years, Chinese finances in Latin America competed as equals with the loans from multilateral financial organizations such as the IDB. This organization has been a significant source of resources to Latin America, consolidating, to some, as ‘the main source of financing to the region development’ (Heine 2020). Only between 2010 and 2020 did it approve more than US $130 billion. And even though during certain years Chinese loans exceeded what was provided by the IDB, as of 2017 this dynamic started to change in favor of the IDB. It is worth noticing that the IDB has also had an important presence in the Andean region, despite the political and ideological differences in the countries. An example is the case of Ecuador during the Rafael Correa administration (Presidencia de la República de Ecuador 2016). However, there have also been problems. The most glaring was the relationship between the IDB and Venezuela, a relationship that was not only affected by the difficulties that the Caracas government had to pay for its credits (to the point that the IDB would have had to suspend loans for non-compliance), but for this organization’s recognition of Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s Interim President.

In this context, the US government assumed that they should have a more active role. Republican Senator Jim Risch, former President of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, mentioned that the United States must compete with China, since its financial presence in developing countries ends up benefiting the acquisition of resources and infrastructure control of great relevance (Kenny and Mitchell 2020). Thus it is no surprise that during the Presidency of Donald Trump, the US government had presented Mauricio Claver-Carone (an American) as candidate for the presidency of the IDB in 2020. This was despite the fact that, since the IDB’s foundation, the presidency always fell on a Latin-American. Moreover, the critical discourse of Claver-Carone against leftist regimes and the influence of Chinese finances in Latin America produced great concern on the politicization of one of the main sources of resources to the region countries. Despite the opposition of a group of countries, Chile and Peru among them, Claver-Carone was elected.

There are several reasons that can explain the weakening of the Chinese financial presence in Latin America, and specifically, in the Andean region. On the one side, the Asian country seems to focus its financial efforts on the Belt and Road Initiative, and not necessarily on this part of the world. Considering the importance of this project inside the dynamic of global competition with the United States, it does sound credible. Additionally, the reduction of Chinese loans could be result of doubts created about the payment capacity that countries could have as the result of the covid-19 pandemic – the cases of Venezuela and Ecuador can be representative. Although, as we have already seen, the Chinese distancing from the region did not start in 2020, but some years before.

This does not imply that there is no Chinese financial presence. In the Andean region, loans from the Chinese private banks have concentrated in Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Colombia. Additionally, there is the interest that the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) generates in the region. Under Chinese leadership, this organization has more than 80 member countries. Among its partners are Ecuador (2019), Chile (2021) and Peru (2022), meanwhile Bolivia and Venezuela are in process of accession. AIIB has financed 167 projects for an amount of US$33 billion, with Ecuador as the first Latin American country in receiving financing from this bank (Aquino y Osterloh 2022) (Harán 2021).

Technology Competition

The rapid advance of China in the innovation and technology field has placed it as the main competitor of the US. Its budget for research and development represents 21 per cent of global spending. It is also the country with the greatest number of registered patents, and its researchers produce more than 18 per cent of global scientific publications (Rosales 2020). To the well-known Belt and Road Initiative, the “Digital Silk Road” project has been added. Focusing on the diffusion of new Chinese technology to the world, this new initiative is in line with the “Made in China 2025” plan, which seeks to diminish the technology gap between the Asian country and the traditional technological powers. Therefore, it is not a coincidence that Chinese companies own 40 per cent of essential patents for fifth-generation networks (5G), necessary to the development of autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, internet, new energies and data control (Balbo and Cesarin 2019).

The advance of China in the technology field has provoked a response from the United States. Initially, Washington sought to reduce the number of licenses related to exports of technologically sensitive products. But the most important measure was the reactivation of the “entity list” which forbids American companies to negotiate with firms that are on said list, due to the danger they represent to national security. Since 2019, the number of Chinese companies listed has increased rapidly, with Huawei being one of “the most dangerous” (García and Tan 2021). Chinese investments in technological sectors are still scarce in Latin America, despite the fact that China’s decision to extend its Belt and Road Initiative allowed 12 of the big companies of the “Digital Silk Road” to operate since 2015. Huawei, Xiaomi, China Telecom and ZTE are some of the main companies in the communications sector in the region. This has allowed the existence of investments in data centers, telecommunication networks and safe cities projects (CEPAL 2021).

Huawei is an important case for being a well-positioned company worldwide, but it also faces espionage charges in the US (López-Peña and Mora-Vega 2019). Since this company has a 5G system which facilitates massive accumulation of information and access to confidential data, it ends up presenting as a threat to the US. Trump’s campaign involved pressure mechanisms to his allies to block any business with Huawei. As a consequence, the US promoted the “Clean Network” project which seeks American government allies and partners to unite against the aggressive intrusions of the Chinese Communist Party. Keith Krach, former Undersecretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy and Environment, pointed out that, thanks to this program, a set of countries in the world now use only trusted providers in their 5G systems, leaving Huawei aside (US Department of State 2020).

It must be noticed that Huawei has been present in the region for almost 20 years, and that is why it is not surprising that the first approaches of Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru to the 5G infrastructure have been given alongside Huawei. Even when the deployment of 5G technology in the Andean countries is in its initial phase, a problem that affects its dynamism is the lack of equipment for the network, and excessive costs. And here, Chinese brands such as Huawei and Xiaomi have an advantage. Despite the aforementioned, the United States has managed to get Ecuador to join the “Clean Network” initiative. The conversations on the 5G project in Ecuador that were led by Huawei, ZTE and Nokia seem favorable to the Finnish company, even though former minister of Economy and Finance of Ecuador, Mauricio Pozo, may have said that all companies were welcomed to participate in the CNT antennas concession, key to the development of 5G infrastructure (Torres 2021). In any case, it seems that the conditions on the US$3.5 billion loan that Ecuador received from the International Development Finance Corporation (a US government agency) during the pandemic, such as “do not use any kind of Chinese technology in your telecommunications network” (Fortin, Heine and Ominami 2021, 25), has had a desirable effect for the US.

The Chilean government has defended a neutrality policy regarding 5G network bidding. And this is how Huawei announced in 2020 the creation of a second data center in Chile, in addition to the construction of a 5G fiber optic network by 2024 (CEPAL 2021). This could serve the rest of the neighboring countries, as well as consolidating (even more) the technological presence of China in the Andean region. In the case of Colombia, former Minister of Information Technologies and Communications Sylvia Constaín said that the country will not restrict companies from bidding or awarding a contract to build 5G, despite the recommendations expressed by the US ambassador, Philip Goldberg, on the risk of allowing unreliable providers. In this way, as part of technological competition, China’s advances in the region and US intentions to contain these are noticed. Certainly, these together represent a concern for the Andean region, and mainly in terms of the 5G networks in the hands of Huawei.

Political Competition

The publication of the second white paper on the policy of China with Latin America and the Caribbean (2016) reflected the commitment of the Asian country towards these countries, seeking to widen its presence in the region. To some academics, it seemed a demonstration of the Chinese attempt to dispute with the United States the hegemony in its historical “backyard”. But this should not be exaggerated, since Latin America, compared to other regions of the world (those linked directly to its Belt and Road Initiative), does not represent a priority for China. And while Latin America has always had a particular importance for the United States (its area of direct influence), in recent times it has lost importance compared to other regions that have presented more important challenges for US foreign policy. It should be noted that unlike the United States, with a presence and influence in Latin America since the 19th century, China has been strengthening its ties with the region only since the 1990s – using two pillars of great impact: the development of political contact spaces and the promotion of intergovernmental mechanisms that allow dialogue and cooperation (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China 2016).

In the Andean region, the political dynamic at the highest level between authorities has been important. In this sense, it is noteworthy that all the Andean countries, with the exception of Colombia, have received President Xi Jinping on an official visit. Visits from high-ranking representatives of Chinese politics have been constant in the last decade, something that did not happen before the 21st century. In the case of Colombia, it is not surprising that one of the main allies of the United States in Latin America since the days of the “respice polum” (“look to the north”), has not received the same attention from China as the rest of the countries. If we compare it with Peru and Chile, its other partners in the Pacific Alliance, ‘Colombia is the most backward and lagging country in establishing direct relations with the Asia-Pacific, this including China’ (Bruce 2017, 10). As part of the contact that has been developed at the bilateral level, in the last decade most presidents of the Andean countries have made official visits to China. In this sense, unlike the United States, China has been more willing to try to build ties regardless of political and ideological differences that may exist.

For the United States, links at that level with leftist governments, such as Correa, Morales or Maduro, have been difficult. For obvious reasons, President Barack Obama only visited Chile, Colombia and Peru – allies of the United States. Although Donald Trump planned a visit to Peru to participate in the Summits of the Americas, and then to Colombia, they were cancelled. Trump’s preference was again shown for the same countries as the previous administration, although with much less interest. Ironically, Trump’s attitude may be contradictory since it was him who revived the Monroe Doctrine in a UN General Assembly, stating that “in the Western Hemisphere, we are committed to maintaining our independence from the intrusion of foreign expansionist powers” (in clear allusion to China and Russia), but he did not seem to have done much about it.

As for the second pillar of Chinese foreign policy, China has developed intergovernmental mechanisms with all the Andean countries. Probably the most important instrument is the construction of alliances that attempt to transcend the traditional bilateral relationship. In the Andean field, China has a Cooperative Association with Colombia, a Strategic Association with Bolivia, and an Integral Strategic Association with Chile, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. China does not seem to take ideological differences into consideration, but rather its own interests, although it is not by chance that, once again, the relationship with Colombia is the least relevant. On the other hand, regarding the presence of China in Latin America at the multilateral level, the China-CELAC Forum (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States), established in 2014, ‘consists of the main diplomatic initiative to strengthen relations between both actors in the regional sphere’ (Bonilla and Herrera-Vinelli 2020, 181). All Andean countries are members of CELAC. It should be noted that CELAC is an intergovernmental tool that emerged to promote dialogue and cooperation between the countries of the region without the presence (and influence) of the United States.

Another space that was intended to be built is the link between China and the Andean Community (CAN), a representative organization of the Andean world. At the beginning of the 21st century, a Political Consultation and Cooperation Mechanism was established, meeting on a couple of occasions at the level of deputy foreign ministers. Over the years, this dynamic has been losing presence, to the point that an institutional political relationship at the highest level between China and the CAN is practically non-existent (Reyes 2015, 171). Evidently, the differences between the member countries of the CAN in recent decades have not been able to consolidate a solid link with China, prioritizing the bilateral relationship. In the case of the United States, there are no major advances either. The differences it has had with some of its members in recent times (Bolivia, Ecuador, and especially Venezuela until its withdrawal from the CAN) have prevented anything from being built in this regard.

Finally, another multilateral entity that has been relevant in the region is the Pacific Alliance (PA). For the purposes of the Andean region, its importance lies in the fact that three of its four partners are Andean countries (Chile, Colombia and Peru). Created in 2011, the PA has sought to promote free trade among its member countries. Therefore, it is not a coincidence that all the PA countries have free trade agreements not only with each other, but also with the United States. And, although the US has no direct participation, except as an observer, its influence seems to be important. In this way, considering the role that the PA has had in the construction of a balance of power with other spaces such as ALBA or MERCOSUR, there are those who consider the PA as a project of the United States, even more so after the failure of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) (Ugarteche 2011). The PA also seeks to become, as indicated in its Framework Agreement, a platform for articulation with Asia-Pacific. This makes the relationship with China a priority, especially for countries like Chile and Peru. Although there have been rapprochements between China and the PA since its admission as an observer state in 2013, there has not been much progress. At some point, in Chinese business and academic circles, the possibility of carrying out negotiations on a free trade agreement between China and the Pacific Alliance would have been considered (Xiaoping 2015, 56), but this was not possible. In any case, to China this link may be of geopolitical importance, not only for the access to resources that the PA countries can offer, but also to counteract and balance the presence of the United States.

Even though there is much to be developed in the political links between China and the Andean countries, whether at the bilateral or multilateral level, progress is evident in both directions. Meanwhile, in this last decade, the traditional influence of the United States has continued, although limited especially to its relationship with some Andean countries such as Chile, Colombia and Peru.

Military Competition

In terms of military matters, Latin America has been a region with a great American influence. Nevertheless, as in other fields, the presence of China is growing. Regarding military acquisition, at the Andean level, the link that China and Venezuela have established stands out. While during the government of Hugo Chávez Venezuela tried to diversify its military purchases (historically linked to the United States) by making Russia a key partner. In the last decade, the government of Nicolás Maduro ‘has made China the main supplier of arms to Venezuela, ahead of Russia’ (Blasco 2017). The Venezuelan government has indicated its desire to buy more Chinese weapons, but economic difficulties have prevented it from doing so (Badri-Maharaj 2019).

Following Venezuela, in recent times Ecuador has also begun to acquire planes and military transport vehicles, trucks, tankers, patrol boats, and AK-47 rifles from China (Ellis 2018, 27). The Rafael Correa administration increased the spending on defense and military purchases, but it also diversified its purchases with different countries: helicopters from India and planes from South Africa and Brazil, among the most important ones (Plan V 2018). Something similar happens in countries like Peru and Bolivia, where the Chinese military presence is still small, but larger than in the past. China would be seeking to supply modern equipment at highly competitive prices, making purchases very attractive. This is even more important considering the objections that the United States would have to transfer state-of-the-art military technology to Latin America (Badri-Maharaj 2019). The case of Colombia is different, not only because it is, after Brazil, the country with the highest military spending in the region, but also because of its well-known military alliance with the United States. Although its military purchases constitute a smaller percentage of military spending, it is the leader in Latin America in this area and the United States is its main supplier.

On the other hand, in terms of military cooperation, China’s rapprochement with all the Andean countries has increased in recent years. This has occurred through cooperation agreements on various topics ranging from the formative aspect, the donation of resources and military material, the exchange of experiences, the management of natural disasters, to technology transfer. Regarding military cooperation with the United States, the US with almost all the Andean countries, with the exception of Venezuela and Bolivia (Isacson and Kinosian 2017). The differences that the governments of both countries have had with Washington for most of the 21st century have prevented any rapprochement. In the case of Ecuador, during the administration of Rafael Correa (a political ally of the Caracas and La Paz regimes), military cooperation with the United States was affected, mainly after the decision to terminate the bilateral cooperation agreement for the use of the base in Manta by the US armed forces in 2009. With Correa’s departure from power in 2017, military cooperation between Ecuador and the United States has been renewed.

It is worth noting that, in the last decade, military aid resources from US sources have been reduced, as well as the budget of the Southern Command, an agency of the Department of Defense that carries out US military programs in most of Latin America (Isaacson 2021, 3). Even in the Colombian case, for years the main recipient of aid in security matters from the United States in the Andean region, thanks to “Plan Colombia”, as of 2010 this military aid began to decrease (Isacson 2021, 3). In any case, the concern shown by the former Head of the United States Southern Command for what is happening is still relevant, when he pointed out in 2021 that the United States would be losing its positional advantage in the hemisphere due to the increasingly important role that countries like China has, by increasing their actions and influence in areas of the activities of the Southern Command (Faller 2021).

Final Reflections

Although other regions of the world are more relevant for its foreign policy, China’s growing influence in Latin America is becoming increasingly relevant for the United States. Nevertheless, there are still power differences between the two countries that prevent us from thinking China wants to start a stage of direct competition, especially in the “back yard” of the United States. Although, conversely, scholars such as John Mearsheimer (2020) believe that Latin America can become the center of the contest between Chinese and Americans. In this sense, China would seek for the United States to focus its attention on Latin America, in such a way that it stops paying attention to Chinese politics. Whatever the scenario, China’s influence in the Andean countries – of great importance due to its projection towards the Pacific Ocean and as a gateway to South America – has increased considerably in the economic sphere, and depending on the area, in some countries more than in others. China also has an increasing presence through the telecommunications sector, although the United States also has political and economic instruments to move Chinese interests away from the region.

At the political level, while China tries to strengthen its ties with the Andean countries, regardless of the existing ideological differences, the United States maintains a strong presence, especially in those countries historically considered its allies, as is the case of Colombia in the first place, and Peru and Chile after it. The recent election of leftist governments in these countries should generate a lot of attention in the US to this effect. Finally, in the military field, the advances of the Chinese in the Andean world are minor, yet growing. With the exception of Venezuela, regional states have been able to diversify their military purchases and do not depend on a single specific country.

Latin American countries cannot afford to choose between China and the United States. It is in this context that voices that speak about the importance of adopting policies such as “active non-alignment” arise, as it expresses the need to maintain an active role in favor of the interests of Latin America in such a complex world, but without the need to opt for either of the two world powers (Fortin, Heine and Ominami 2021). In any case, whether in the short or medium term, it is very likely that Latin American countries, especially those in the Andean region – relatively small and highly dependent on world powers – will be forced to choose at some point. For Stephen Walt (2021), if the competition between China and the United States intensifies, the countries of the region “will have to choose a side” and will at least come under US pressure to turn from China. Whilst the countries of the Andean region are not yet in such a scenario, it would be wise to prepare for it.

Notes

Thanks are due to Andrea Rivas Huerta, student of the Political Science and Government Program at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, for her valuable collaboration in preparing this document.

References

Aquino, Carlos, and Maria Osterloh. Perú es el miembro latinoamericano que más ha aportado al Banco Asiático de Inversión en Infraestructura. 31 31 January 2022. https://alertaeconomica.com/peru-es-el-miembro-latinoamericano-que-mas-aportado-al-banco-asiatico-de-inversion-en-infraestructura/.

Badri-Maharaj, Sanjay. El mercado de armas de China en América Latina. 2019. https://www.zona-militar.com/2019/08/06/el-mercado-de-armas-de-china-en-america-latina/.

Balbo, Gabriel, and Sergio Cesarin. «¿Guerra comercial, periferia tecnológica o tecnoimperialismo? América Latina ante la competencia global en el sector de las telecomunicaciones.» Memorias del IV Seminario Académico del Observatorio América Latina-Asia Pacífico. Montevideo: ALADI, CAF,, 2019. 24–45.

Banco Central de Chile. «Balanza Comercial por Países, Anual.» 2022.

Banco Central de Ecuador. «Estadísticas de Comercio Exterior.» 2022. https://www.bce.fin.ec/index.php/comercio-exterior

Banco de la República de Colombia. «Inversión extranjera directa en Colombia, según país de origen.» 2022.

Blasco, Emili J. China sustituye a Rusia como principal proveedor de armas a Venezuela. 2017. https://www.abc.es/internacional/abci-china-sustituye-rusia-como-principal-proveedor-armas-venezuela-201704052203_noticia.html.

Bonilla, Adrián, and Lorena Herrera-Vinelli. «CELAC como vehículo estratégico de relacionamiento de China hacia América Latina (2011-2018).» Revista CIDOB d’ Afers Internacionals, nº 124 (2020): 173–198.

Bruce, Viviana. «Relaciones político-diplomáticas Colombia-China: Un escenario inexplorado.» Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana. Seccional Bucaramanga, 2017: 1–14.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ECONOMICS. Table 2.3. U.S. International Trade in Goods by Area and Country, Not Seasonally Adjusted Detail. 21 December 21 de Diciembre de 2021. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?ReqID=62&step=1 (last access: 12 12 March 2022).

CEPAL. La inversión Extranjera Directa en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago: Naciones Unidas, 2021.

Detsch, Claudia. «Escaramuzas geoestratégicas en el «patio trasero». China y Rusia en América Latina.» Nueva Sociedad, 2018: 79–91.

Ellis, R. Evan. «El apalancamiento de Ecuador sobre China para conseguir una vía alternativa de política y desarrollo .» Air & Space Power Journal , 2018: 18–35.

Faller, Craig. «U.S. Southern Command.» Statement of Admiral Craig S. Faller Commander, United States Southern Command. Before the 117th Congress Senate Armed Services Committee. 16 16 March 2021. https://www.southcom.mil/Portals/7/Documents/Posture%20Statements/SOUTHCOM%202021%20Posture%20Statement_FINAL.pdf?ver=qVZdqbYBi_-rPgtL2LzDkg%3D%3D.

Fortin, Carlos, Jorge Heine, and Carlos Ominami. El No Alineamiento Activo y América Latina. Una doctrina para el nuevo siglo. Santiago de Chile: Catalonia, 2021.

Gallagher, Kevin P., Amos Irwin, and Katherine Koleski. «¿Un mejor trato? Análisis comparativo de los préstamos chinos en América Latina.» Cuadernos de Trabajo del CECHIMEX , 2013: 1–40.

García, Alicia, and Junyu Tan. «Competencia estratégica EEUU-China: Del comercio a la tecnología.» Anuario Internacional CIDOB, 2021: 117–125.

Garzón, Paulina, Siran Huang, Stephanie Jensen-Cormier, and Marco Antonio Gandarillas. «Latinoamérica Sustentable.» 2021. https://latsustentable.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Informe-Banco-de-Desarrollo-de-China-LAS.pdf

Ghotme-Ghotme, Rafat Ahmed, and Alejandra Ripoll De Castro. «La relación triangular China, América Latina, Estados Unidos: socios necesarios en medio de la competencia por el poder mundial.» Entramado 12, nº 2 (2016): 42–53.

Gilpin, Robert. War and Change in World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Giuseppi, Charles. «China y Venezuela: Cooperación Económica y Alianzas Bilaterales durante la Era Chávez.» Revista Tempo Do Mundo, 2020: 403–434.

Harán, Juan Manuel. Ecuador and the First AIIB Project in Latin America. December 2021. https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/ecuador-and-the-first-aiib-project-in-latin-america/.

Heine, Jorge. Chile y la batalla por el BID. August 2020. https://www.latercera.com/opinion/noticia/chile-y-la-batalla-por-el-bid/Z6LZXWENMREFTL6FPZLUT2UY64/.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. «Exportaciones Bolivia.» 2022. https://www.ine.gob.bo/index.php/estadisticas-economicas/comercio-exterior/cuadros-estadisticos-exportaciones/

Isacson, Adam. «Fundación Carolina.» Estados Unidos y su influencia en el nuevo militarismo latinoamericano. 16 16 November 2021. https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/AC-28-2021.pdf (last access: 24 24 March 2022).

Isacson, Adam, and Sarah Kinosian. WOLA. 27 27 April 2017. https://www.wola.org/es/analisis/ayuda-militar-de-estados-unidos-en-latinoamerica/

Kenny, Charles, and Ian Mitchell. «Center for Global Development.» 19 19 de Octouber re de 2020. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/problem-isnt-chinese-lending-too-big-its-us-and-europes-too-small (last access: 3 3 April 2022).

López-Peña, Kendall Ariana, and Roy Mora-Vega. «La guerra comercial entre Estados Unidos y China: Un enfrentamiento más allá de los aranceles.» InterSedes, 2019: 236–245.

Mearsheimer, John, entrevista de Leandro Dario. John Mearsheimer: “Es posible una guerra entre Estados Unidos y China en 2021” (25 25 July 2020).

Merino, Gabriel Esteban. «Guerra comercial y América Latina.» Revista de Relaciones Internacionales de la UNAM, 2019: 67–98.

Ministerio de Comercio, Industria y Turismo – MINCIT. «Estadísticas de Comercio Exterior de Colombia.» 23 23 July 2021. https://www.mincit.gov.co/estudios-economicos/estadisticas-e-informes/comercio-exterior-de-colombia

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. «Documento sobre la Política de China Hacia América Latina y el Caribe.» 2016. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/esp/wjdt/wjzc/201611/t20161124_895012.html.

Molina Díaz, Elda, and Eduardo Regalado Florido. «Relaciones China-América Latina y el Caribe: por un futuro mejor.» Economía y Desarrollo 158, nº 2 (2017): 105–116.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. National Data. Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation. 2022. https://data.stats.gov.cn/english/easyquery.htm?cn=C01

Plan V. «El legado del correato en armamento y gasto militar.» 3 3 September 2018. https://www.planv.com.ec/historias/sociedad/el-legado-del-correato-armamento-y-gasto-militar

Presidencia de la República del Ecuador. Rafael Correa: “Nunca se ha trabajado tanto ni tan bien con el BID”. 2016. https://www.presidencia.gob.ec/rafael-correa-nunca-se-ha-trabajado-tanto-ni-tan-bien-con-el-bid/#.

PROMPERU. «PROMPERUSTAT.» Ranking de Países. 2022. https://www.siicex.gob.pe/promperustat/frmRanking_x_Pais.aspx

Pu, Xiaoyu, and Margaret Myers. «Overstretching or Overreaction? China’s Rise in Latin America and the US Response.» Journal of Current Chinese Affairs, 2021: 1–20.

Reyes, Milton. «China y la Región Andina: Dinámicas en el contexto de la integración regional sudamericana.» In China en América Latina y el Caribe: Escenarios estratégicos subregionales, by Adrián Bonilla and Paz Milet, 166–198. San José: FLACSO, CAF, 2015.

Rosales, Osvaldo. El sueño chino. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno, 2020.

Svampa, Maristella, and Ariel Slipak. «China en América Latina: Del Consenso de los Commodities al Consenso de Beijing.» Ensambles, 2015: 34–63.

The Dialogue. The Dialogue. Leadership for the Americas. 2022. https://www.thedialogue.org/map_list/

Torres, Wilmer. «Red limpia ¿Red sucia? Qué pasa con el 5G en Ecuador.» PRIMICIAS, 19 January 19 de Enero de 2021.

U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Report to Congress of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. One Hundred Seventeenth Congress, Washington: U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC), 2021.

Ugarteche, Oscar. El Bloque del Pacífico desde la integración estratégica. 25 25 April 2011. https://revistaizquierda.com/secciones/numero-11-mayo-de-2011/el-bloque-del-pacifico-desde-la-integracion-estrategica

US Departament of State. «Special Briefing via Telephone with Keith Krach, Under Secretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy, and the Environment.» 2020.

Walt, Stephen, entrevista de Leandro Dario. La disputa en 2021 entre EE.UU. y China, según los especialistas (3 3 January 2021).

Xiaoping, Song. «China y América Latina en un mundo en transformación: Una visión desde China.» In China en América Latina y el Caribe: Escenarios estratégicos subregionales, by Adrián Bonilla y Paz Milet, 51–73. San José : FLACSO, CAF, 2015.

Figures

Further Reading on E-International Relations