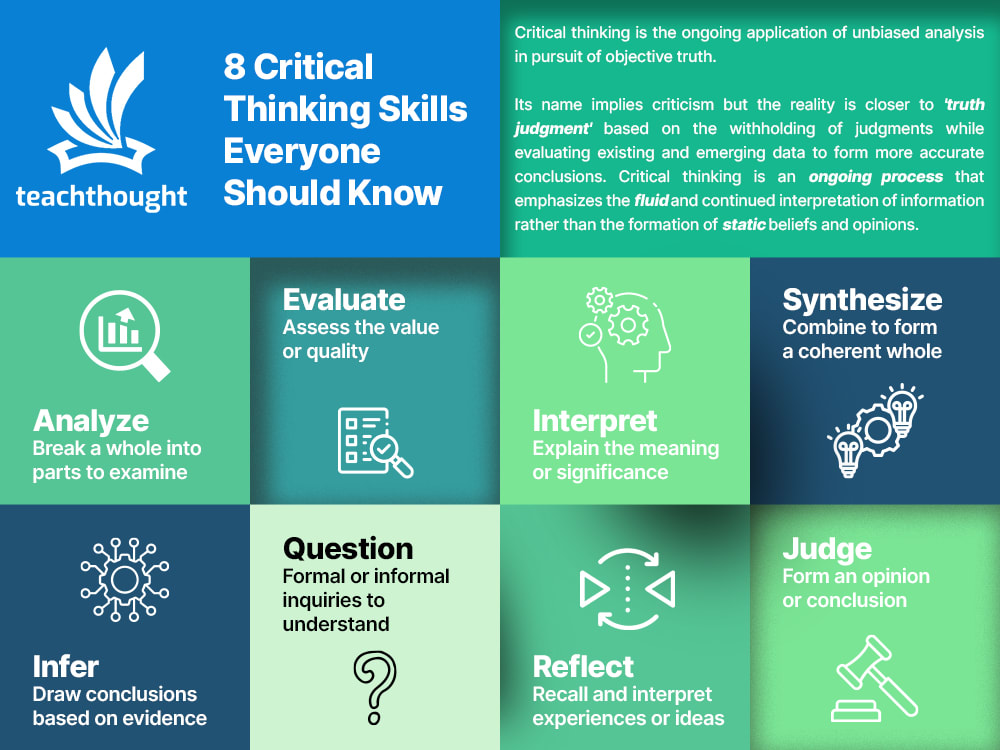

Critical thinking is the ongoing application of unbiased analysis in pursuit of objective truth.

Although its name implies criticism, critical thinking is actually closer to ‘truth judgment‘ based on withholding judgments while evaluating existing and emerging data to form more accurate conclusions. Critical thinking is an ongoing process emphasizing the fluid and continued interpretation of information rather than the formation of static beliefs and opinions.

Research about cognitively demanding skills provides formal academic content that we can extend to less formal settings, including K-12 classrooms.

This study, for example, explores the pivotal role of critical thinking in enhancing decision-making across various domains, including health, finance, and interpersonal relationships. The study highlights the significance of rigorous essential assessments of thinking, which can predict successful outcomes in complex scenarios.

Of course, this underscores the importance of integrating critical thinking development and measurement into educational frameworks to foster higher-level cognitive abilities impact real-world problem-solving and decision-making.

Which critical thinking skills are the most important?

Deciding which critical thinking skills are ‘most important’ isn’t simple because prioritizing them in any kind of order is less important than knowing what they are and when and how to use them.

However, to begin a process like that, it can be helpful to identify a small sample of the larger set of thinking processes and skills that constitute the skill of critical thinking.

Let’s take a look at eight of the more important, essential critical thinking skills everyone–students, teachers, and laypersons–should know.

8 Critical Thinking Skills Everyone Should Know

8 Essential Critical Thinking Skills

Analyze: Break a whole into parts to examine

Example: A teacher asks students to break down a story into its basic components: characters, setting, plot, conflict, and resolution. This helps students understand how each part contributes to the overall narrative.

Evaluate: Assess the value or quality

Example: A teacher prompts students to evaluate the effectiveness of two persuasive essays. Students assess which essay presents stronger arguments and why, considering factors like evidence, tone, and logic.

Interpret” Explain the meaning or significance

Example: After reading a poem, the teacher asks students to interpret the symbolism of a recurring image, such as a river, discussing what it might represent in the poem’s context.

Synthesize” Combine to form a coherent whole

Example: A teacher asks students to write an essay combining information from multiple sources about the causes of the American Revolution, encouraging them to create a cohesive argument that integrates diverse perspectives.

Infer: Draw conclusions based on evidence

Example: A teacher presents students with a scenario in a science experiment and asks them to infer what might happen if one variable is changed, based on the data they’ve already gathered.

Question

Formal or informal inquiries to understand

Example: During a history lesson, the teacher encourages students to ask questions about the motivations of historical figures, prompting deeper understanding and critical discussions about historical events.

Reflect

Recall and interpret experiences or ideas

Example: After completing a group project, a teacher asks students to reflect on what worked well and what could have been improved, helping them gain insights into their collaborative process and learning experience.

Judge: Form an opinion or conclusion

Example: A teacher presents students with a scenario where two solutions are proposed to solve a community issue, such as building a new park or a community center. The teacher asks students to use their judgment to determine which solution would best meet the community’s needs, considering cost, accessibility, and potential benefits.

8 Of The Most Important Critical Thinking Skills

Citations

Butler, H. A. (2024). Enhancing critical thinking skills through decision-based learning. J. Intell., 12(2), Article 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12020016